Gravel Worlds 2022 Race Recap

October 19, 2022

Streaking: Is it for You?

November 26, 2022Unlike biking and running, skill is more important than fitness when it comes to swimming. Developing skills takes time, patience and determination. In endurance sports, economy refers to the physiological cost of swimming, biking or running, expressed in liters of oxygen per unit of distance. As an athlete improves their fitness, the amount of oxygen at a given pace drops. You may think of this as efficiency.

Small changes in economy can produce dramatic changes in performance. So, to become a better endurance athlete, the key is to become more economical, or waste less energy.

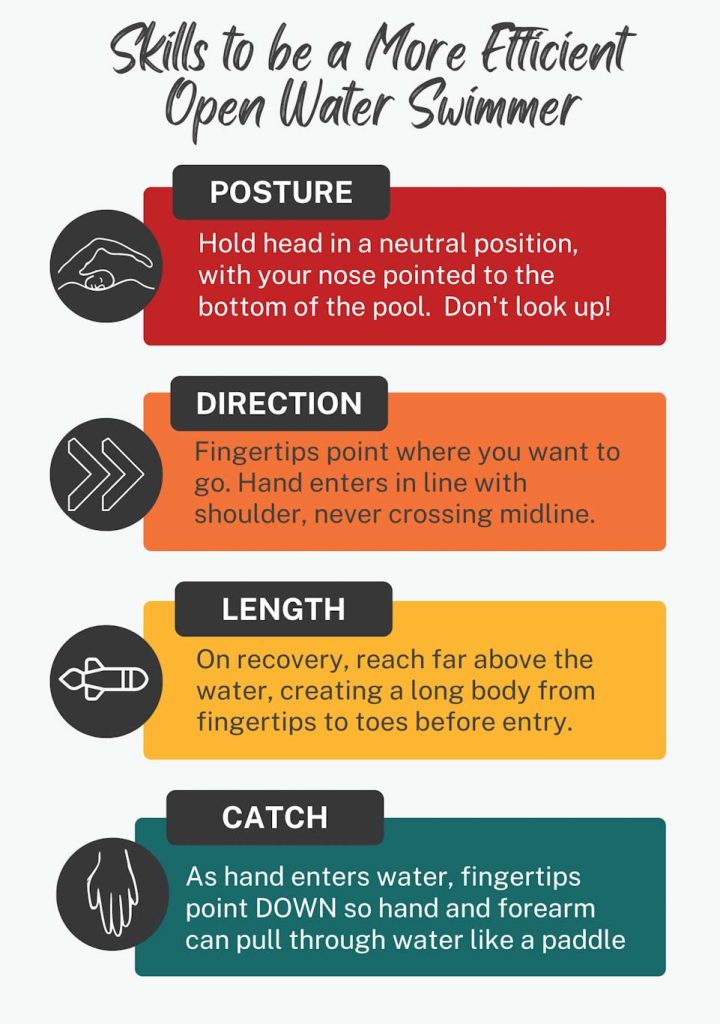

While there is an endless number of swimming skills one could focus on, Joe Friel, author of the Triathlete’s Training Bible, names position, direction, length and catch – as the top skills needed to become a faster, more efficient open water swimmer. He collectively calls them PLDC.

Before we delve into the skills, keep in mind that open water swimming skills differ from pool swimming skills. A pool is a controlled environment, but triathletes swim in rivers, lakes and oceans. The focus for triathlon swim training should be on elements that are critical in varied environments. So, some of these skills may be contrary to what you had previously been taught.

Friel’s PLDC assumes that the athlete has mastered the front crawl breath. Until an athlete can breathe with their face underwater, there is little benefit to moving forward or adding aerobic endurance training – which is where most endurance athletes want to start. If we did that we’d only be reinforcing bad skills. So, first, learn to exhale with your face in the water.

Each of these skills will help your swimming, and also make breathing easier! Try focusing on one new skill each week, mentally before you get in the water, during your swim and then recalling how you felt during the swim-session afterwards.

POSTURE

Posture in the water is is governed by your head. Hold a neutral head position, with your nose pointed to the bottom of the pool. Most triathletes look ahead at the approaching wall, which causes the legs to drop, creating drag and slowing you down. A head up posture also makes it harder to breathe. Make sure to keep your focus on the bottom of the pool and use the lane lines to keep you straight.

Don’t move on to the next skill until you have mastered posture.

DIRECTION

Direction is a skill that improves efficiency and helps you to swim straight in open water. The simple guide is that your fingertips should point in the direction you want to go. The hand should enter the water in front of your shoulder, not in front of the head, and never cross the midline of the body.

If the hands cross the midline of the body we start to snake our way through the water. Imagine a runner who crosses one leg in front of the other on each step – terribly inefficient!

This may be a harder skill to master. Stick with it before you move on. Practice on dryland before you get in the pool. Hinge from the hips and reach as if you’re taking a stroke. See where your hand lands. Make adjustments using a friend or video to assist. In the water, the penguin drill is helpful to eliminate crossover.

LENGTH

Length builds speed and efficiency. A longer stroke helps you get more distance but also facilitates rotation and breathing. Once you’ve mastered posture and direction, move on to length.

Length refers to how long your body is in the water from fingertips to toes. The more long and narrow you become, the faster you will swim. Stand facing a wall, just a few inches away. Raise your arm like you’re taking a stroke with the other arm at your side. Now look at your hips, are they square to the wall? If they are, reach even higher, as high as you can reach. This causes your shoulders to tilt and your body will rotate naturally.

Picture a 10 year old kid that really knows the answer to teachers question – that kid is raising their arm with their entire body! That’s the length you want to achieve.

Watch a professional triathlete swim in open water, you will notice their arms appear to be straight out of the water and they reach as far as they can above water before their hands enter. This technique helps athletes access the ever elusive “high elbow” and causes your body to roll toward its side – the hip rotation you’ve been trying to master for so many years.

CATCH

An efficient catch increases your pulling power and speed.

The catch is the initial phase of the freestyle stroke, where the hand enters the water and begins the underwater part of your stroke (the pull). The catch influences the rest of your freestyle stroke.

As the hand enters the water, fingertips should point down towards the bottom of the pool so the hand and forearm can immediately start to pull through the water like a paddle. What most triathletes do is push their hands straight down for the first half of the stroke – wasting precious energy.

Try flexing your wrist just as your extended hand enters the water. Point your fingers toward the bottom of the pool and then pull straight back. Don’t be concerned with the ‘S’ patterns.

LEARN MORE

I’d highly recommend Friel’s Training Bible for anyone interested in long-course triathlon – even if you are working with a coach. He offers excellent practical advice which will likely complement what you do with your coach.

I’m personally a big fan of audiobooks and this is a great listen too!

This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to purchase after clicking a link, I may receive a commission at no extra cost to you.